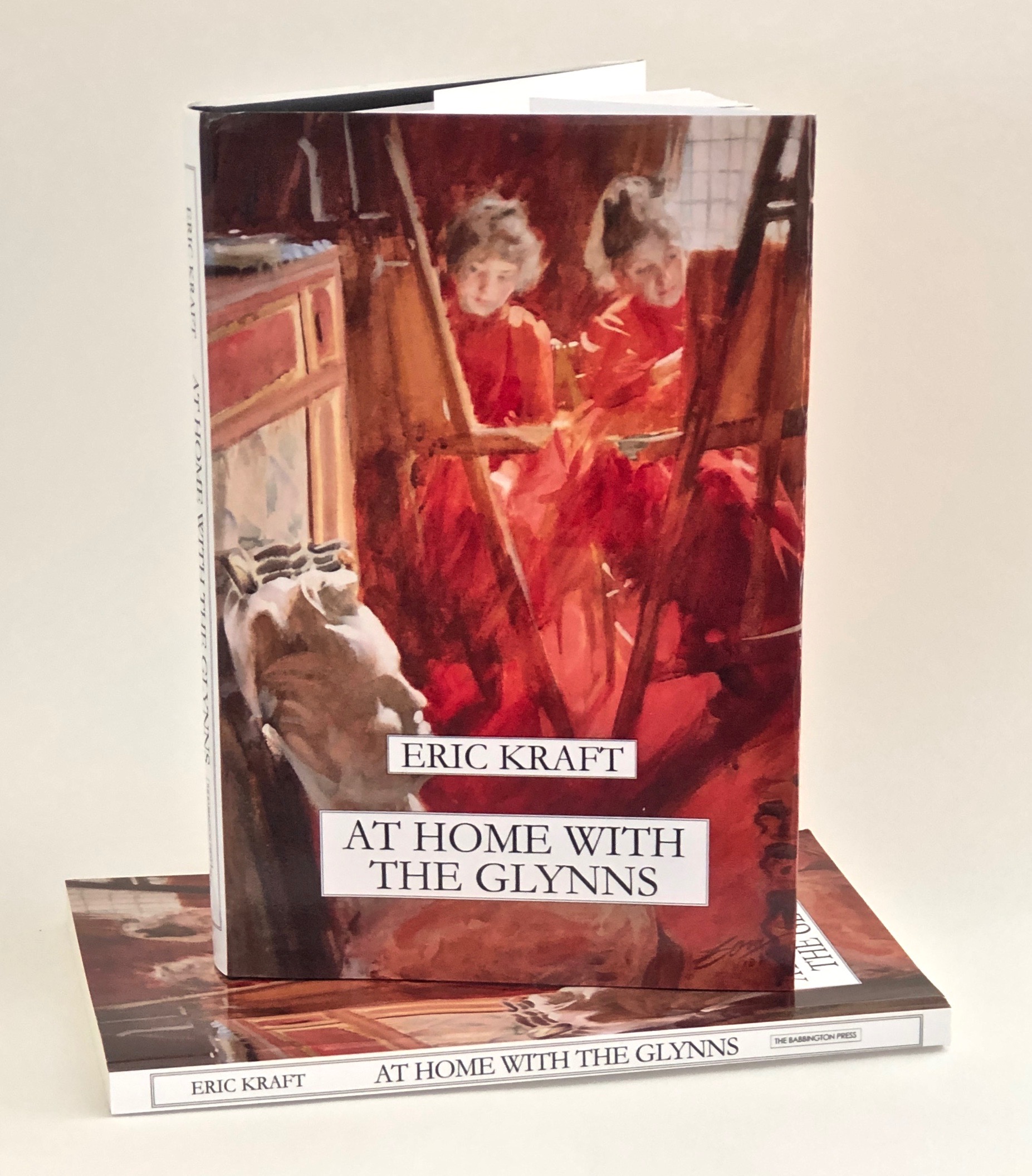

AT HOME WITH THE GLYNNS

(A Novel)

By

ERIC KRAFT

“This gently provocative novel uses a boy’s delicious dalliance with two sisters to serve up the author’s true passion: Deep Questions about the nature of art and memory.”

Kirkus Reviews

Anders Zorn, Les Demoiselles Schwartz (1889, detail)

“A daring tour de force. . . . Mr. Kraft’s cunning novel is really a children’s book (like, say, The Catcher in the Rye) for adults, which I mean as unequivocal praise. ”

Jonathan Baumbach, The New York Times Book Review

“The comedy of At Home with the Glynns comes equally from the boyhood tale, which cheerfully flouts all the literary laws of childhood innocence, and from the adult narrative voice in which it is slyly recounted. With self-mocking finesse, the novel celebrates the savor of memory for the sophisticated palate.”

Boston Sunday Globe

A Sample

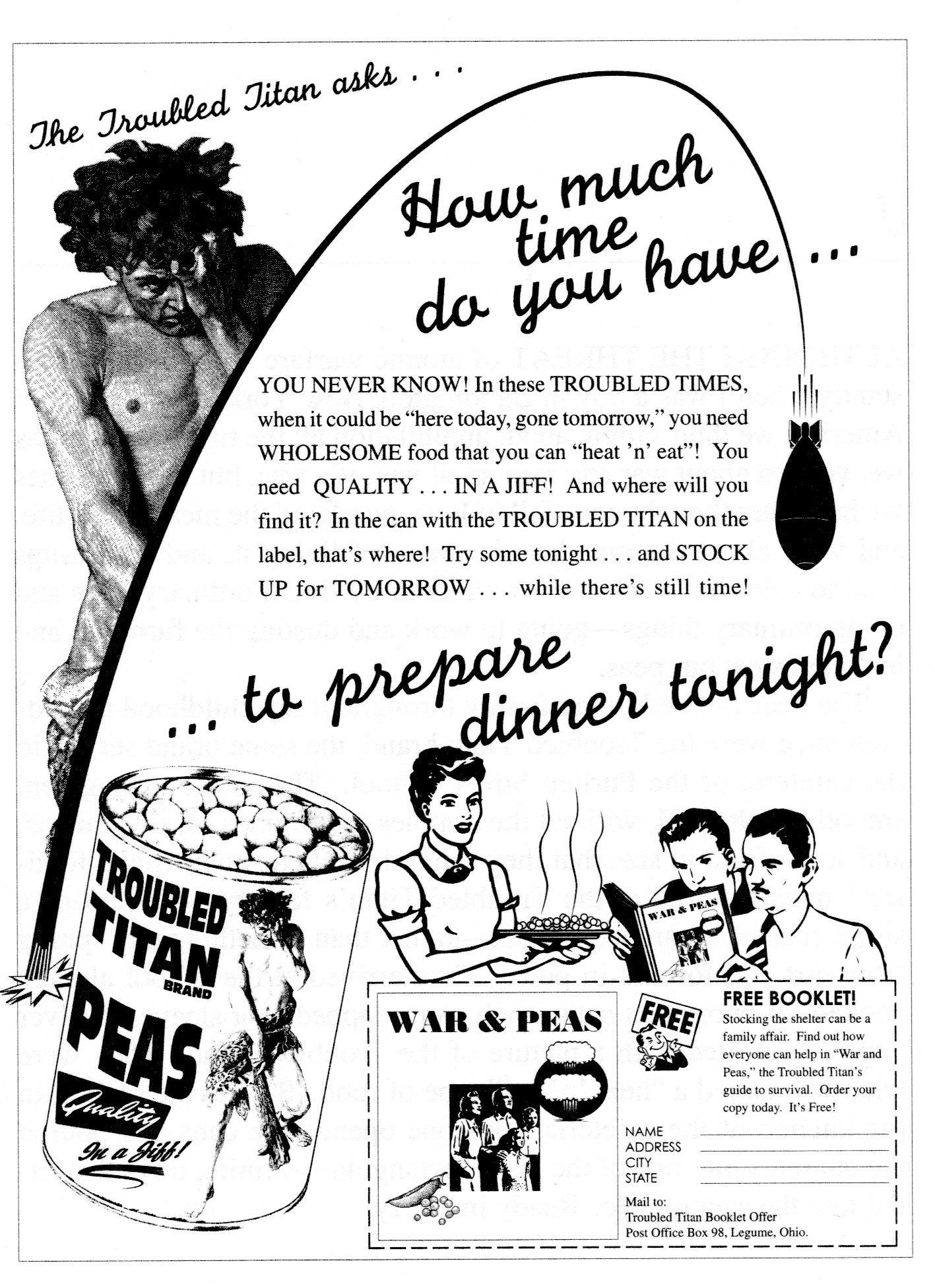

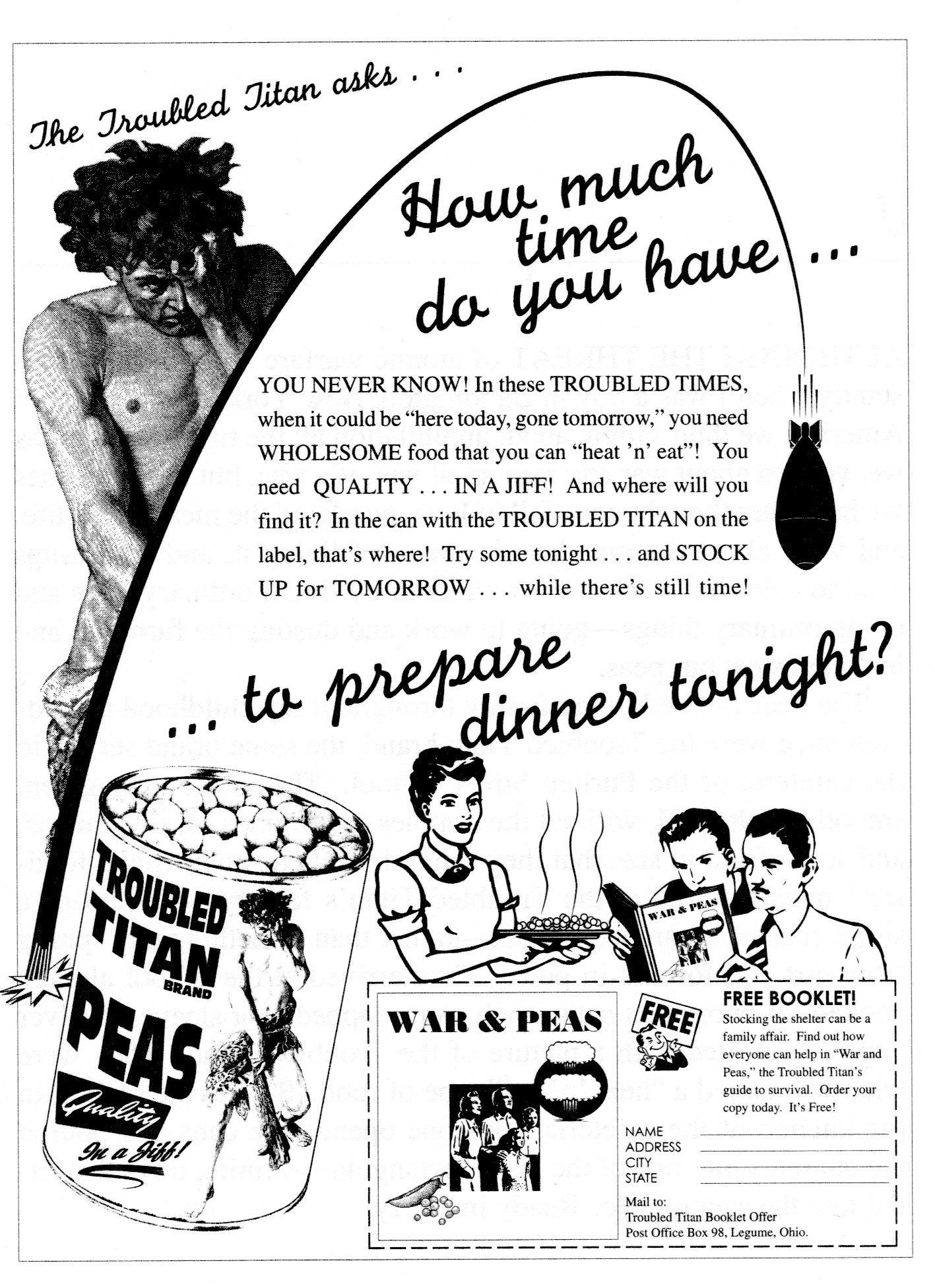

ALTHOUGH THE THREAT of atomic warfare hung over us constantly when I was a boy in Babbington, New York, clam capital of America, we didn’t think about annihilation all the time. Sometimes we worried about war and rumors of war, it’s true, but at other times we had other thoughts: we fell in love, pondered the meaning of life, and went about the mundane business of living it, and grown-ups tried to calm the fears of their children by living ordinary lives and doing ordinary things—going to work and dusting the furniture and making us eat our peas.

The peas favored in my family throughout my childhood and adolescence were the Troubled Titan brand, the same brand served in the cafeteria of the Purlieu Street School. They were gray-green, smoothly spherical‚ without the dimples or wrinkles of, say, raisins, and so uniform in size that they might have been an artificial foodstuff manufactured at the Troubled Titan’s factory—replicas of a single master, an archetypal pea—rather than something that sprang from dirt and formed in pods. They arrived at the school already cooked, in enormous cans, each can wrapped in a sleeve of silver paper, imprinted with a picture of the Troubled Titan. They were what was called a “heat ’n’ eat” type of food. Behind the scenes, in the kitchen of the cafeteria, someone opened the cans and poured the contents into one of the large rectangular warming trays that fitted into the steam table. Ready in a jiffy!

ONE DAY I was in the cafeteria at the new junior high school, making my way along the steam table in a line with the other scholars, collecting the various components of my lunch: half a pint of milk in a waxed cardboard container shaped like a cabin in the woods; two slices of white bread; a square pat of butter on a square of white cardboard with the edges bent up to make a little tray, with a square of thin translucent waxed paper stuck to the top; one slice of roast beef as thick as a nickel, marbled like a topographic map, gray as the sheet of cardboard around which Spotless Cleaners folded my father’s Sunday shirts, with gravy; mashed potatoes, also with gravy; and those Troubled Titan peas. A woman in a hair net dished the peas out onto my plate lukewarm and wet. The pea water, gray-green like the peas themselves, spread instantly, making an island of the mashed potatoes, mingling with the gravy.

Of the many things that puzzled me about school, one was that the common sense so prized in society at large in those days never seemed to penetrate the doors of the school building. Watching the pea water and the gravy interswirl, I wondered why the divided plates that my family used on picnics were not used here in the school cafeteria, where they were really needed. Finding myself wondering along those lines, I thought of suggesting the use of divided plates to one of the ladies in the hair nets, but I decided against it, because the time that I’m recalling was a time when young people generally kept their mouths shut.

Occupied by my thoughts, I took a seat at a table that was otherwise unoccupied and set my tray on the table. I was observing the spread of the pea water when Margot and Martha Glynn arrived and sat on either side of me, Margot on my right and Martha on my left.

“Are you right- or left-handed, Peter?” asked Margot without preamble.

“Well,” I said, “I write with my right hand but I throw a ball with my left, so you could say I’m—”

I paused slightly, because I enjoyed the word I was about to say and was proud of the skill it summarized.

“—ambidextrous.”

“That’s good. Ambidextrous is good,” said Margot.

“But those are useless skills,” said Martha.

“Yes,” said Margot. “What about rolling peas?”

“Rolling peas?” I had the feeling that a joke was coming.

“Try it,” said Martha. She picked a pea from her plate with the tip of her spoon and let it roll onto the table between us. Margot did the same with one of hers.

“Now rest your finger on that pea,” said Margot. “Martha’s, too.”

I put my index fingers on the peas.

“This one,” said Martha, taking the middle finger of my hand and placing it on her pea. Margot made the same change on her side.

“Just rest your finger there lightly,” Margot cautioned. “Don’t squash the little thing.”

I did as she said.

“The same over here,” said Martha.

“Good,” said Margot. “Now let’s see you roll the peas around a little.”

Cautiously, I began to move my fingers on the peas.

“Close your eyes,” said Martha.

I closed my eyes, and I found that that helped. The peas seemed larger, more easily manipulated. I had a better sensation of the feeling of each pea against the finger pad that rested on it. I seemed to acquire a sense of the difference between the skin of the pea and the mush it contained, to understand the tensile limits of the skin, the edge of the danger of rupturing it, and the resistant resilience of the ball of mush within. I became a little bolder, rolling the peas a little farther, a little faster—and the right one got away from me.

“Don’t get cocky,” said Margot. “Just move them around a little. Don’t try to impress us.”

“You’ve got to walk before you can fly,” said Martha. “Try again.” Humbled, I moved the peas gingerly, maintaining control, moving them ever so slightly, just keeping each pea on the central ridge of my finger pad, never rolling so far that the pea would slip away. . . .

“Faster over here,” said Margot.

“And slower over here,” said Martha, “but with longer strokes.”

“Okay, let me see. I—oops—I—”

“He squashed mine,” said Martha. There was in her voice a note that I wouldn’t have expected. I might have expected her to be annoyed with me, or I might have expected her to be amused, but she was—and this was unmistakable—disappointed.

“What do you think?” she asked Margot.

“He can do it if he concentrates,” she said. “I really think he can.”

“Practice at home.”

“Practice at home?” I asked.

“You have peas at home, don’t you?”

“Sure, but—” I had intended to say that I wasn’t allowed to play with my food, but when I looked into Margot’s doubting, inquisitive eyes, I saw that such an objection was inappropriate. I looked at Martha and saw the same thing in her eyes.

“But?” she asked.

“Well—why?”

They looked at each other. They looked at me.

“Just to please us,” said Martha.

|

| |

Scroll down for another sample.

“Readers . . . will find Kraft’s wry style, deep insights into youth and age, and sly observation of adult behavior a rare delight. . . . Anyone who has mourned, or yearned for, his or her younger self will find Kraft an enchantment.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Another Sample

ROSETTA GLYNN greeted me at the big wooden door when I returned on Saturday afternoon. She wore a look that I recognized: the look of someone with a story to tell, sizing up her audience with bright, curious eyes. . . .

She took a seat at a round table that still held the remains of lunch. No one else was around.

“Have something,” she said.

She waved her hand across the table and finished the gesture by letting her hand fall limply onto a cigarette pack, which she lifted as if it were considerably heavier than the cigarette packs my parents had around the house. She took a cigarette from the pack, and while she went through the business of lighting it, I took a roll from a pile of several on an earthenware platter. The roll had an unfamiliar shape. I took a bite. It had an unfamiliar flavor.

“Mm, this is good,” I said. “What is it?”

She exhaled and squinted through the smoke. An odd look came over her face, part grimace and part smile, a look of grudging reminiscence, as if she couldn’t keep herself from remembering, though she would really rather not.

“Well,” she said, and shrugged, “it’s a roll. . . . To you, it’s a roll.” She looked at me and raised an eyebrow.

“Uh-huh,” I said.

“But it’s more than that, you know,” she added, and she winked and waved away some of the smoke. “Much, much more.” She paused. “To me—to me, it’s hope.” . . .

She got up from the table with a weary sigh and went to a cupboard over the sink, where she got a fancy bottle with a circular body. I tried to read the label, but the words all seemed to be misprinted or backward, and the largest word was nearly obscured by an elaborate drawing of vines. As well as I could make it out, it seemed to say SLIVOVITZ, but that didn’t match any words I knew, so I assumed that I was wrong. From another cupboard, she got a tiny tumbler, no bigger than a shot glass, but thin and fragile and delicate and ladylike. She returned to the table, set the bottle and the tiny glass down, sighed, smiled a queer, funny, endearing twisted smile, shook her head, sat, uncorked the bottle, filled the tiny glass, and set the bottle down beside the glass.

Then, apparently on impulse, she took another roll from the platter, broke it in half, and held the halves to her face. She drew a long breath, inhaling the aroma of the roll.

“Smell it,” she said.

I did as she had done. The aroma was wonderfully rich and yeasty, almost too much for me.

“That’s hope you smell,” she said. She put the roll back on the platter and said, “I’ll tell you why I say that.” She lifted the glass, took a sip, and said, “We had to get out, of course.” She looked for some sign of understanding from me. “You know,” she said.

I didn’t, but I nodded and said, “Mm.”

“The Fascists,” she said.

“Oh!” I said. “Yeah.” I knew who they were, in a way. They had been the bad guys in the war comics, the official enemies of our tribe, before the Gooks, Chinks, and Russkies came in.

“Yes, yes. That’s why. The Fascists. Andrew—but of course he wasn’t Andrew then—was a marked man, a very comical man, very funny. He was a cartoonist then, you know. A caricaturist. He was very popular—very, very popular. He was even in a nightclub, as an entertainer. He would go around and make pictures of people—not just the way someone would go around and sell you cigarettes or take your photograph. No, he was a performer, with a spotlight on him. Such a big man, you know.”

A smile, a sip.

“He had a pad of paper mounted on a board that he held in the crook of his arm—like this—and in a hole in the board a pot of paint. Black paint. One big brush. And he would make his pictures with big gestures—like this—big swooping gestures. His pictures often appeared in the papers, too. Very often. People always laughed, even the people he drew. They were flattered to have him make their pictures. They were happy to join in the laughter at themselves because—because they were—people. We like attention, you know, people, and we know how ridiculous we are. It’s one of the ways you can spot us. You catch us laughing, and you know we’re human.” She leaned toward me through the smoke. “It’s a dead giveaway,” she said.

She poured a little more into the tiny tumbler.

“Then those Fascists came in,” she said. “Andrew made such comical pictures of them all—those Fascists. For the papers, you understand. And then, pretty soon, they ran all the papers—those Fascists. And they didn’t want to look comical. So he made his drawings for the walls. Huge.”

She looked up at the stone wall and swept her hand to indicate the grand size of Andy’s caricatures and shook her head at the inadequacy of her gesture. I thought of the scaffolding in the studio and the enormous size of the painting he was working on. “Uh-huh,” I said. “I understand.”

“Good,” she said. “Huge caricatures, and more comical than ever. He painted by night. And he signed his pictures with a little drawing of a bat.”

She took a sip. “Well, you know, there was a price offered, a price offered for him, for ‘The Bat.’ Money, you know. When money is offered, you would be very surprised how cheap you can buy someone. How cheap it is to buy a betrayal. Trust comes dear,” she said, “but treachery is cheap.”

She took a sip. There was a long silence. I had no idea what she was talking about, so I had no idea what to say.

|

| |

“The book is an exploration of time, memory, truth, and trust, and Kraft is a master of dialogue and description.”

Town and Country

“A splendidly vivid exploration of ‘sexual pleasure amplified and augmented by the thrill of adventure’—a striding tour through a young boy’s mind as he enters what he calls ‘that enchanted Glynnscape.’”

Dwight Garner, New York Newsday

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

“Nostalgic and very funny and just a little perverse. . . . Kraft manages, as always, to pass his serious concerns off with the delicate evanescence of a bubble blown from a ring.”

Frederic Koeppel, Memphis Commercial Appeal

Read complete reviews.

“Miraculously, Kraft weaves every disparate strand into a tightly knotted yarn.”

Malcolm Jones, Jr., Newsweek

|